Joshua

for saleHistory of the Joshua

The French sailing legend Bernard Moitessier (1925–1994) gained considerable publicity after writing Vagabond des Mers du Sud, in which he shared several of his views on ocean sailing theory. Jean Fricaud, a shipyard owner experienced in using steel as a boatbuilding material, contacted Moitessier and offered to build him the “perfect” boat, charging only for the cost of the steel and welding rods. Having lost his previous boat in the Caribbean, Moitessier was excited by the offer—but he also wanted to be involved in the project.

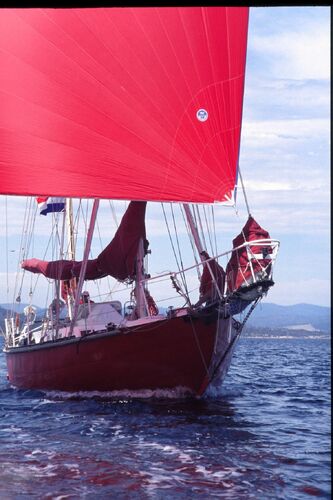

Moitessier wanted a double-ended hull to better handle the breaking waves of the open ocean. He also preferred the ketch rig, due to its smaller sail area and flexible sail plan. After some debate—Moitessier initially wanted a smaller vessel—Knocker drew the lines. Fricaud then designed the steel construction, including two watertight bulkheads. Moitessier decided to name the boat Joshua, a name that later became associated with the entire boat type.

It's important to note that the shipyard built only the hull and installed the engine. Moitessier was short on funds at the time, so his first masts were made from telephone poles. The boat was completed in 1962, and after earning some money through his sailing school, Moitessier set off with his wife to sail around the world. Upon returning to France, he wrote the widely acclaimed book Cape Horn – The Logical Route. This occurred shortly before the first Golden Globe Race, which itself gained significant publicity after Francis Chichester agreed to act as its overseer. In his memoirs, Moitessier recounted that he was, in fact, pressured to participate in the race—as France’s answer to the British and as the country’s own sailing hero.

Youtube: Joshua de Bernard Moitessier

Youtube: French sailor Bernard Moitessier

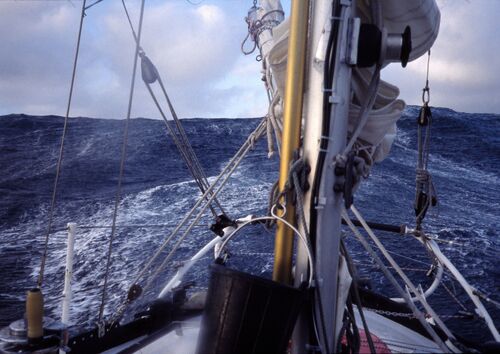

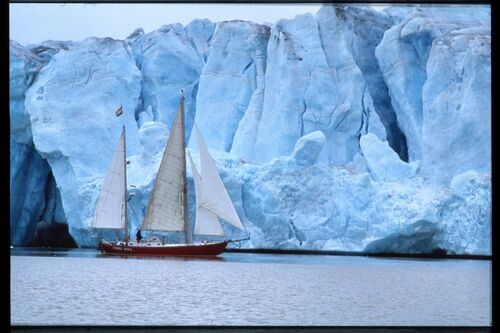

Several books have been written about the first Golden Globe Race, most of which focus heavily on the personalities of the sailors. After sailing downwind around the globe, Moitessier learned of his position near the latitude of Argentina and realized he was likely to win the race. However, the Frenchman wished to preserve his peace of mind and instead turned for a second circle, heading once more toward the Cape of Good Hope. Joshua reached Tahiti after more than 300 days at sea, and Robin Knox-Johnston went on to win the race. All of this has been told many times. Moitessier’s decision to abandon the race undoubtedly added to his and Joshua’s legendary status. Today, the boat is part of the La Rochelle maritime museum’s collection—and it is still being sailed.

Brief History of the Terra Nova

The history of her is exceptionally well-documented. The boat was built in 1968 at Jean Fricaud’s META shipyard. The first owner was a doctor from Milan, who had the interior fitted by an Italian boatbuilder. An oversized rig was commissioned from Ian Proctor. The first owner completed one downwind circumnavigation with the vessel before eventually selling it to a couple from Berlin. This stage of the boat’s life is the least clear, but a receipt found on board confirms a payment made in Panama.

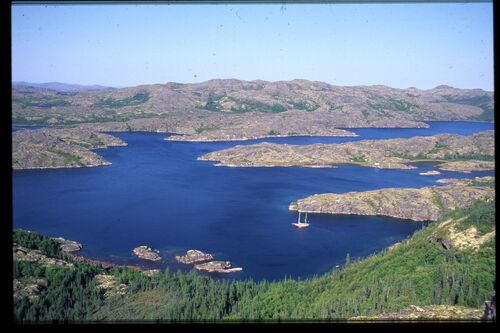

From that point onward, the boat's history is well known. In 1983, she was purchased by a Dutch sailor who embarked on a 2½-year voyage around the world, traveling via Panama and the Suez Canal. He wrote travel reports for Zeilen magazine, and these issues have been preserved. In 1987, Dutch couple Corri and Willen Stein bought the boat and completely dismantled it down to the bare hull. Terra Nova was designed in such a way that it can be taken apart without causing damage.

The couple then sailed around the world with the boat until 2007, when they settled in New Zealand. They documented their voyages in various sailing magazines. Once their travels were complete, they put Terra Nova up for sale—and the next owner was found in Finland.

Dimensions

12.07 x 3.60 m, LOA 15.30 m, draught 1.60 m, lightship around 14 tons.

Hull

Fricaud used the same construction method in every Joshua, where the hull was welded in a rotatable "cradle." The hull is shaped like a wine glass, and the bottom of the keel is a flat 23 mm steel plate, which is 40 cm at its widest. The next plate upward is 15 mm, then 9 mm, and finally 6 mm all around. The steel plates run the entire length of the boat from bow to stern and are overlapped by 50 mm, with weld seams on both sides. In addition, there are frames every 50 cm, even though they are not structurally necessary. Moitessier's requirement was two watertight bulkheads. Inside the keel, steel ingots are stacked. The idea behind the construction was that if the yacht ran aground on a coral reef, the sailor could lighten the boat one ingot at a time and get free. The ballast is located under a welded grid, so it stays in place even if the boat capsizes. The entire hull is galvanized. The yard sandblasted the hull and then "sprayed" it with molten zinc. Since then, the boat has never been sandblasted again! Fricaud and Moitessier’s idea was that the hull wouldn't even be painted. Because of the galvanization, the paint peels off in large flakes, as shown in the photos, and can be gently removed with a wooden scraper. The photos probably say more about the condition of the hull.

Hull Openings

In the toilet, there are two pipes, with the solid pipe extending above the waterline. This allows them to be cleaned while the boat is in the water. Both ball valves are made of fiberglass-reinforced plastic by Forespar, and there have been no issues with them during winters when the boat has been in the water.

The galley’s water outlet valve is stainless steel and located above the waterline. It also serves as the drainage outlet for the cockpit. The engine's intake valve is also stainless steel, and the water flows through a bronze siphon valve from the top. Cooling water exits on the starboard side above the waterline.

The propeller shaft has standard stuffing box seals, and the shaft runs to a very robust pressure bearing, for which a drawing exists. For lubrication, there is a lubrication pipe and a fixed grease press in the engine room. The bearing has likely never needed to be opened.

Watertight Bulkheads

In the forward section, at the front end of the saloon, there is a removable door that is secured with four threaded bolts. Between the saloon and the engine room, there is a hinged steel door.

Deck Openings

At the bow, there is a Goiot-brand aluminum hatch, with spare seals stored on the boat. The cockpit hatch features a Goiot “observation dome,” which can be secured from the inside. The previous owner greatly appreciated this hatch after the boat capsized on the voyage from Cape Town to Australia—it was reassuring to check in rough weather that the rigging hadn’t been damaged. The only loss was the torn doghouse canvas.

At the stern, there is an aluminum hatch that can also be secured from the inside, with a solar panel mounted on top. All three ventilation openings are Goiot and have rubber plugs that can be compressed into place for rough weather. One spare Goiot vent is included among the spare parts. The cockpit hatch has rails that allow it to slide forward, so it can be kept open or left slightly ajar.

Windlass, Anchors, and Chain

The windlass is manufactured by the Italian company Orvea. The anchor chain is galvanized and an impressive 13 mm thick, with 75 meters stored in its dedicated locker. The chain is marked, and its other end is secured to the boat with a rope loop, allowing it to be sacrified in an emergency. The main anchor is a genuine 50 kg Bruce. A second anchor is stored in the bow locker and can also be used as a stern anchor. There is a dedicated roller for it and for a drogue anchor.

In the saloon bilge, there is a Luke-brand collapsible Admiralty anchor, which proved effective when the boat overwintered on rocky ground in Svalbard. The windlass can be operated from the deck via a control cable.

Lifting Eyes

There are four lifting eyes on the deck, with structures that extend down into the hull. When lifting the boat, long slings under the hull are not needed. The boat comes with four short lifting slings and shackles.

Steering System

Inside the steering pedestal, there are two gears connected by a chain. This is the only part I would consider redesigning—replacing it with a Harley Davidson–style toothed belt might be more practical. The steering cables loop around the tiller from the outside, making them very easy to replace, even at sea. The turning blocks have been replaced and now feature stainless steel plain bearings.

Aries Wind Vane

Nick Franklin developed the Aries wind vane in the 1960s, and there are several "generations" of the design. The first generation was made of bronze, but the material proved too expensive. He then switched to aluminum and created casting molds designed to be extremely durable. Terra Nova’s wind vane is from this second generation. In the third generation, material thickness was reduced, and most Aries wind vanes found on boats today are from that third generation. Since Franklin’s death, the manufacturer has changed at least twice.

Terra Nova comes with all the spare “wear parts,” and if more are needed, a machinist can produce them at a significantly lower cost. It's also worth noting that the wind vane is very well protected from harbour collisions (and from other yachts).

The wind vane blades wear over time, but they can be made from marine plywood, allowing experimentation with different materials. The boat is also equipped with a traditional tiller-mounted autopilot, which is connected to the wind vane blade. I’ve never used it myself, but I’ve heard it works.

In newer generations, the servo rudder is "flip-up," but Terra Nova has the older model, where it must be removed manually. The servo rudder shaft and mounting sleeve are made of stainless steel. The boat also includes an aluminum "breakaway sleeve," designed to protect the system if it hits fishing nets. A spare servo rudder is stored in the bow locker.

The wind vane can be adjusted from the cockpit using control lines. Instruction on how to operate the system is, of course, included in the price of the boat.

Winches and Gear

Behind the cockpit, there are two large Maxwell winches made of bronze. They were chrome-plated a few years ago. I recently acquired two stainless steel Andersen winches for the front of the cockpit, of which only one has been installed so far. The other could be mounted on the main mast, as hoisting the sail with the gearless Lewmar halyard winch can be tough on the shoulder when sailing solo.

Both masts are equipped with traditional drum winches. The blocks are made of stainless steel—the same type used by trawler fishermen.

Sails and Rigging

All sails are new North Sails (Niiniranta), and the specifications ordered were for ocean sailing at high latitudes. The sails have been stored in a warm place during the winters. The boat also comes with the old sails, of which practically only the spinnaker and storm sail are still useful.

The furling headsail was made by Facnor. The rigging is completely original and was manufactured by Proctor. According to the previous owner, the rigging was designed for a 50-foot boat. Bernard Moitessier visited Tahiti on this boat, and before his fourth glass of wine, he praised Terra Nova’s rigging highly, saying, “If only I had had one like this.”

Engine, Gearbox, and Shaft

The Perkins Prima (M50) was installed in 1995. The engine has been very well maintained—not just in words, but this can be verified from the maintenance logbook. It has 6,466 running hours. The boat also includes the factory service and repair manual, which describes all repairs step by step in addition to routine maintenance. There is a large stock of spare parts.

The gearbox is made by ZN, and its design allows free rotation while sailing. The shaft has a Scatra universal joint, with wear parts replaced less than a hundred hours ago. The manufacturer of the thrust bearing is unknown, and it likely has never needed to be opened. However, there are drawings available.

In the engine room, there are two fixed grease presses used to apply grease to the shaft and thrust bearing. The shaft is sealed traditionally with stuffing boxes. A spare propeller is also kept in the engine room. On the propeller shaft, there is a small alternator that helps maintain battery charge while sailing. This is sufficient for conservative electrical consumption.

The photos also show that access around the engine is easy. The bilge has its own dedicated drain plug.

Tanks

Tanks There are three fuel tanks. Below, around the propeller shaft, there is a tank of about 50 liters. This tank has a manhole and a drain plug, making it easy to clean when the boat is on dry land. On the port side, there is a 250-liter tank that “feeds” into the lower tank. It also has a large manhole and can be thoroughly cleaned by hand. The tank features a “sight glass” that allows the fuel level to be checked. On the starboard side, there is a 200-liter tank with a similar sight glass to check the fuel level. Switching between tanks is easy with a single lever.

Above the large tank on the left side is a dedicated tank of about 40 liters for the Dickinson Alaska stove. Currently, there are only two fuel filters in the line, but in the engine room’s spare parts cabinet there is a U.S.-made “farm filter” ready to be installed if traveling in areas where fuel cleanliness is uncertain. The boat also has an uninstalled Racor 1000 filter with a filtration capacity sufficient for years. However, using it requires a booster pump, which is not expensive.

The aluminum water tanks (250 + 250 liters) are located under the saloon and are accessible through manholes. The manhole covers are transparent, making it easy to check the tank status. Under the corridor, there is an emergency tank of about 100 liters, which can be put into use if needed.

Water for the galley and the forward sink is pumped by foot pumps, which have spare parts available. The sink water can also be pumped out. Due to regulations, there is also a septic tank in the bow.

All pumps on the boat are manual. The water, fuel, and kerosene tanks are filled from the deck and have bronze screw caps.

Forward Watertight Compartment

The anchor chain is stored in a fiberglass locker with a drain valve at the bottom for water removal. The space between the locker and the hull can be cleaned. Currently, the bow serves entirely as storage and a workshop. The photos probably explain everything.

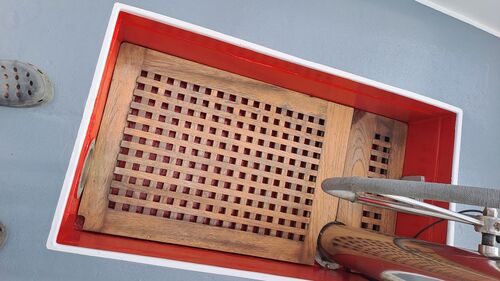

Under the teak grating, there is a stainless steel “basin” for wash water. The toilet bowl and flushing mechanism are made by Lavac. The bowl is vacuum-pumped. Compared to many other systems, its operation is very reliable, but using it requires some initial practice. The boat also has a spare toilet bowl cover with seals.

In rough seas, those who have used the toilet will appreciate the sideways “tightness” of the space. Opposite the toilet is a deep copper sink and a wardrobe.

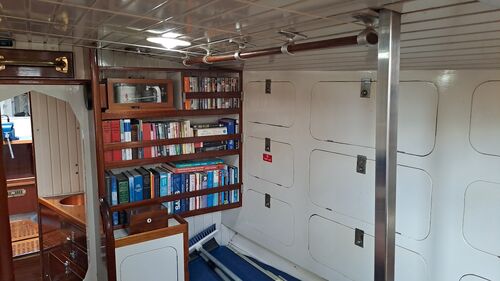

Saloon

On the port side, there is a sea berth with a high removable railing, which is stored in the forward ceiling. The starboard sea berth is built so that the backrests can be moved onto supports. How to use it becomes clear on the boat.

There is plenty of storage space on both sides of the saloon and under the seats—much more than is typical in boats of this type. The navigation station is on the starboard side, and this boat features a full-sized chart table with drawers.

On the starboard side is the galley, equipped with a two-burner Primus kerosene stove. It runs on lamp oil—there is no gas on the boat! Next to the stove is a dedicated kerosene tank of about 30 liters, which can be filled through a deck pipe. Although the stove requires some know-how to operate, it means you don’t have to worry about refilling gas bottles. Plus, kerosene is available in every less-developed country.

There are two deep sinks, supplied with water via a foot pump from the aft water tank through a filter. Both foot pumps are the same model, as are the four manual hand pumps on board.

Under the galley is a “cellar.” There is no refrigerator in the galley. In the engine room, there is a high-quality compressor-powered cold chest. Without external electricity or solar panels, the Lifeline 215 Ah service battery has lasted three days at 50% discharge. I have never allowed it to go below that.

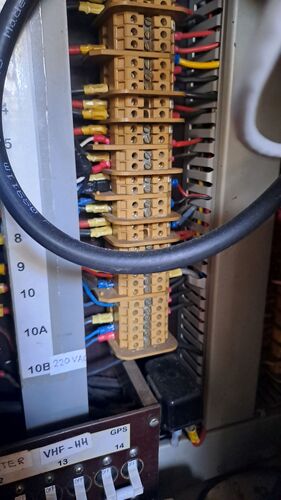

Navigation Station

The full traditional marine chart can be opened on the chart table, which has five chart drawers underneath. Currently, the boat has three separate GPS units: two at the navigation station and a third at the steering wheel. There is nothing special about them.

As a professional mariner, I have extensive experience with radars, and the Furuno GaAs is an excellent radar. I have navigated busy buoy lanes in the Netherlands in dense fog using it without any problems.

The boat is equipped with a SAAB AIS Class A unit, which has not been installed due to radio licensing restrictions. Class A is mandatory on the open ocean. Most sailers don’t realize that large vessels often block Class B data from their ECDIS devices, which means smaller boats are not be visible!

The VHF radio is a brand-new Sailor 6222 DSC, which also has not been connected. Additionally, the boat carries a Sailor SP3510 VHF handheld radio.

There is also an SSB radio with a separate antenna tuner box located at the mizzen mast.

A recording barometer and traditional echo sounders are on board. A dedicated space for a computer screen has been left at the navigation station.

The steel hull acts as a Faraday cage, and the mizzen mast carries a high-quality omni antenna with excellent cabling and a router.

Aft Cabin

When designing the boat, it was important to separate the saloon activities from a quiet sleeping area. As the pictures show, there is storage space under the double bed, with deep storage lockers on both sides.

Remaining Details

Let’s review them together. The boat is currently in Kemiönsaari (Finland), and the plan is to drydock it in July. The deck was painted in 2024 with a two-component paint.

I have tried to give as clear a picture as possible of the yacht’s features above, but everything should still be reviewed together. When I bought the boat from the Stein couple in New Zealand, I made sure there were no obligations from the European VAT regulation. The boat was built in France and was registered in the Netherlands when sold. It has been in the Finnish boat register since 2009.

Corri and Willem Stein wrote humorously, “if you are looking for a multibunk comfort container, then she is not for you. But if you want to sail in safety in any oceans or latitudes, then she is for you.”

Price

You never get your money back on a boat, especially not the hours of work put into it. I have updated the boat to be ready and don’t foresee any significant future expenses. Only some of the electronics need to be connected due to radio licensing. Replacing the chain in the steering pedestal might be worth considering for easier handling.

The starting point for negotiations is €125,000.

I will only take personal belongings from the boat, and everything else will be agreed upon together — including arrangements for the drydock.

Contact Information

Hannu Vartiainen

Master Mariner

+358 50 358 8611

hannu.vartiainen@gmail.com